Curating The Story of Anne Innis Dagg: How 400 Boxes of Archives and Reels of Found Footage Made Movie Magic

With 400 boxes of files at the University of Waterloo, stacks of personal letters and hours of found footage on 16mm film from the 50’s, the story of Anne Innis Dagg in The Woman Who Loves Giraffes is one that took a fierce storyteller’s eye and ear to curate.

Director Alison Reid tells Anne’s story beautifully by featuring voice-over recordings of personal letters, read by Victor Garber (Argo, Milk, Titanic) and Tatiana Maslany (Orphan Black) woven together with still photos, reenactments, and present day footage of Anne in the midst of her re-entry into the scientific world and an emotional return to Africa.

“Going through the archives took a long time and everyone was like ‘when are you gonna be done?’ … I’m really glad it took as long as it took because parts of her [Anne’s] story unravelled over these five years.” Alison remembers.

Like any epic story, Alison’s research needed a starting point.

She began with the letters exchanged between Anne and Mr. Matthew, the South African rancher that gave Anne residence despite being a single woman traveling without a chaperone, over their decades long friendship.

When Pursuing Giraffe, just one of the many books authored by Anne, was published in 2006, Anne gifted a stack of personal letters to the surviving Matthew grandchildren who in turn created a beautiful book of those letters.

One of the more profound moments in Anne’s story was uncovered in one of the letters found at the University of Waterloo.

Sandy Middleton, a tenured professor at the University of Guelph in the 70’s, wrote an apology letter to Anne for her denial of tenure in the zoology department.

He expresses guilt over the rejection of her application and attempts to comfort Anne by letting her know she is a deserving candidate, despite the decision.

Sandy also laments the secrecy that is afforded the tenure committee proceedings and that they are regretfully not obligated to publicly justify their decision. This was the beginning of Anne’s professional heartbreak and lifelong battle with sexism in higher education.

Anne, a self-proclaimed pack rat, also provided valuable material to Alison, most importantly several old reels of film in aged yellow boxes.

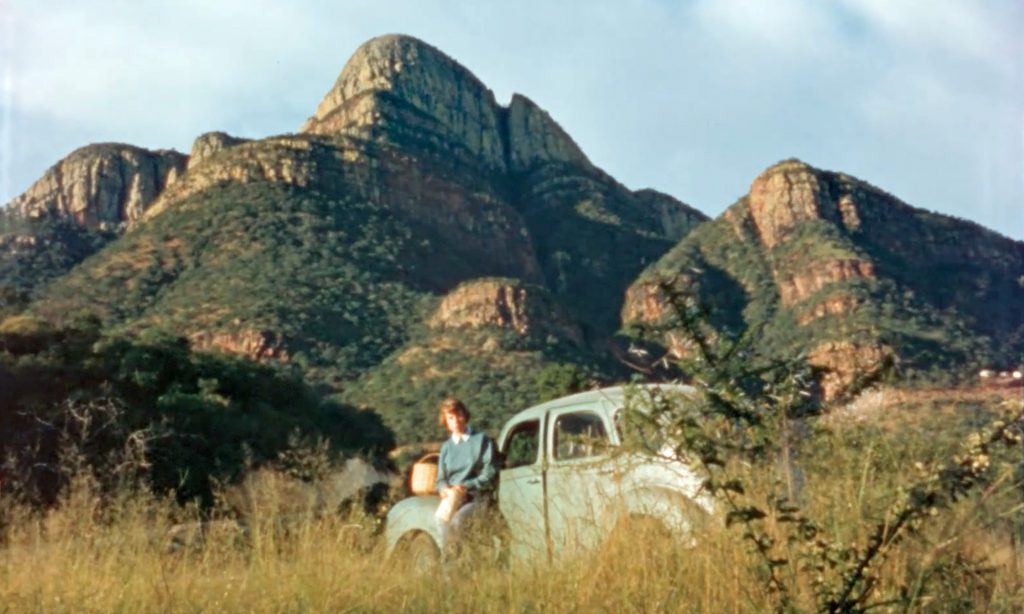

Much of Anne’s study of giraffe was captured on these films, including footage of young Anne roaming the savannah with her beloved giraffe, her trustee old car ‘Camelo’, and her life on the ranch with Mr. Matthew.

The original film cans and boxes are used in the film re-creations, lending the scenes warmth and authenticity.

“I’d been in contact with Anne a lot throughout the process because she’s got, you know, a lot of things around her house and she’s always trying to cull. She’s like ‘I have too much stuff. I just want to get rid of it’ and one day she says, ‘there’s these film cans, I don’t know what they are. Can you get rid of them?’ They were big reels, [not in the little yellow boxes], so I took them not knowing what they were.” remembers Alison.

With little money yet raised for the making of the documentary, Alison hesitated to spend money digitizing more reels but eventually bit the bullet.

It turned out to be well worth the investment.

It turned out to be well worth the investment.

Captured on these reels was footage of Anne famously draping giraffe intestines across a wash line to measure and study as well as the first footage ever of giraffe ‘necking’, or fighting, and other behaviours used in her PhD.

Additional footage of life at Fleurs de Lys (the ranch) was sent to Alison from surviving grandchildren of Mr. Matthew who still live in South Africa.

They recovered footage of Anne in some of her daily chores, she exchanged administrative work for board, and scenes of workers going about their daily business on the ranch during the time of the birth of Apartheid.

Part of the magic of this film is the switching back and forth between past and present.

Alison used moments of young Anne back in the 50’s in Africa and mirrored them next to present day re-creations with Anne on her return trip in 2013.

“I found a fixer, a woman who works in film and lives in that area (in South Africa) and I was able to send her screenshots of parts of the 16mm film. ‘Here’s the office, here’s these mountains that we have this 16mm footage of. Can you find these places?’ And she went back and she found me those places… The part where the bed and breakfast is [at Fleurs de Lys] doesn’t even have giraffe anymore. Sad. But what was part of the original Fleur De Lys now contains game reserves such as Kapama.”

The significance of Anne returning to her passion of ‘giraffing’ some 50 years later is evident in these moving re-creations.

Many of the locations remain physically the same with the only visible change being an older, wiser, present day Anne with the distinct glow of a woman who has returned to her true love – the study and conservation of wildlife, and her beloved giraffe.